For this year's Remembrance Day services, four Sixth Form History of Art pupils kindly accepted the important task of preparing reflections to deliver to St Peter's Senior School and guests on Tuesday, November 11th.

Two historically significant works of art were chosen (see below) and included in the programs given to all in attendance for reference. The connections made between the pieces and the lessons we can all learn from them made for two brilliant and memorable Remembrance services in honour of all 127 Old Peterites who died in action, as well as all others we remember who gave their lives in service.

Well done to Emily, Sylvia, Meg, and Emilia for their hard work and well-written speeches. We wanted to share their pieces below for all to read and reflect upon, please enjoy.

Artworks

Paul Nash (top). 'We are Making a New World', 1918

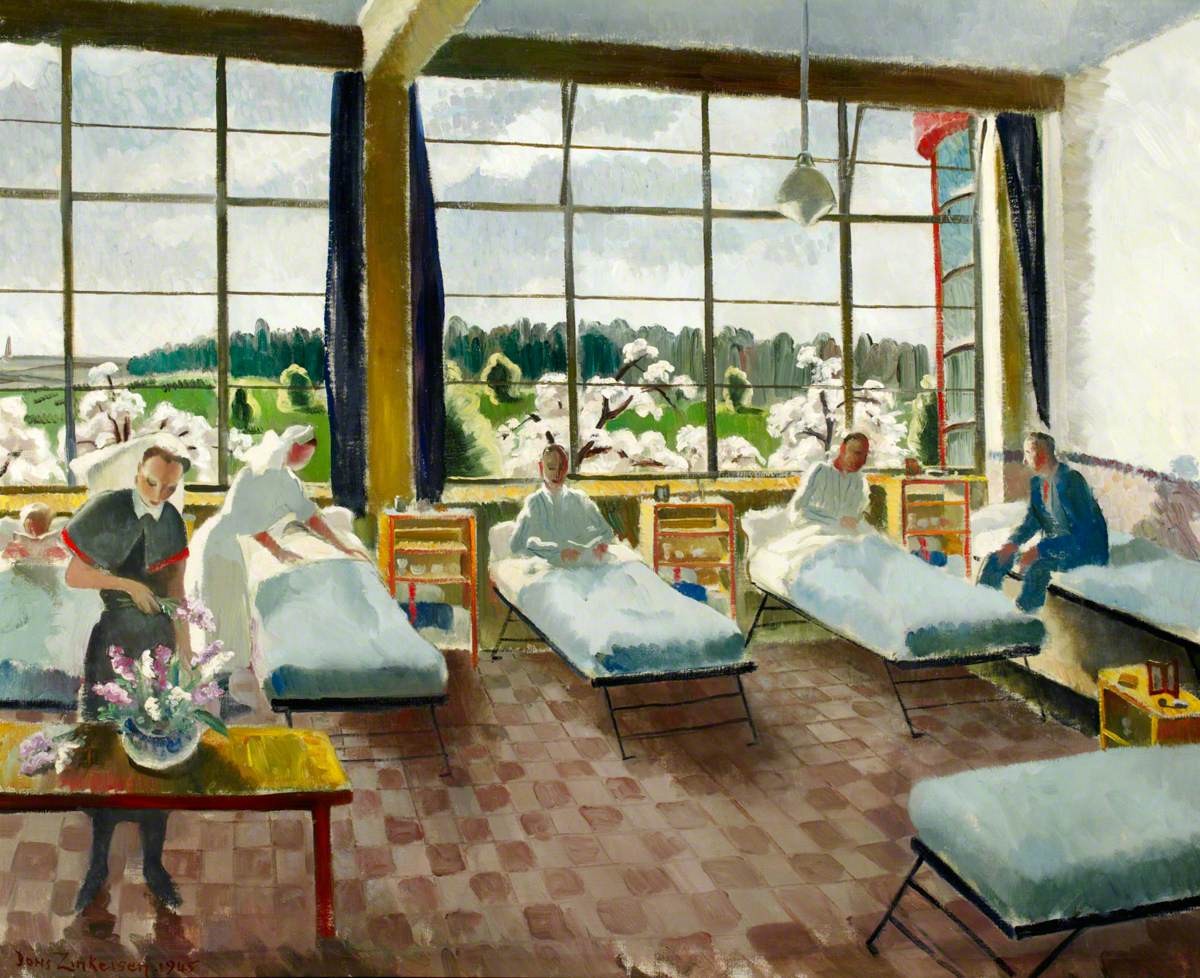

Doris Zinkeisen (bottom). 'C-Ward 101 of the British General Hospital, Louvain', 1945

Junior Service Speeches

Meg - Art can be used to tell many stories, ones of pain, love and sacrifice, particularly in times of conflict. Art can help us look back at previous and present conflicts and confront the horror of war not with acceptance but with understanding. Today especially we can gather to look further, not only to history books and memorials, but to the power of art and the individual stories it tells, giving voice to the unspeakable.

One way we can look to see how art tells a story is through World War one artist, Paul Nash. He himself was a soldier, from 1914 to 1917 until he was injured in France and then moved back to England becoming the official war artist, his brother John was also an official war artist. Documenting on the front line not only the historic events but capturing the emotion behind these moments. If you look to the order of service- in one of his most famous pieces ‘We are Making a New World’ from 1918 he depicts what war was really like from his first-hand experiences. Instead of showing soldiers fighting, he painted a broken, muddy battlefield with smashed trees. He reminds us of those lost to war, and those who lived through it, represented by the decay of the trees. His painting tells a story of pain and bravery, so that we can learn from the past and hope for peace in the future.

Emilia - However, the experience of war can be far more varied than just brutal conflict and the work of Doris Zinkeisen records just how different a female perspective was. Volunteering as part of the British Red Cross, Doris nursed victims of the Blitz in World War Two- however, showing a strong talent in art from a young age, she was commissioned by the War Artists Advisory Committee to also record and remember the activities of the Red Cross during this conflict through art. Offering her services when the portrayal of war was typically a man's work, her work offers a completely different

understanding of the many impacts of war. If you look to the order of service- Her picture of C-Ward 101 of the British General Hospital in Louvain, creates a moment of quiet- in contrast to Paul Nash, she shows a sense of hope. Theres a woman changing a vase of flowers, but none are dead- nature outside is blooming and the hospital is lit with bright, clear colours- we are not invited to see any of the darkness of war- not even in the patients. This work instead remembers the recovery and renewal that follows conflict. Her image captures the work of volunteers and nurses that silently and importantly supported post-war relief. She reminds us that conflict can always come to an end.

War art has many vital purposes- forcing us to confront the horrors of conflict and the reality of it. The legacy of these images ensure that we do not lose such important memories- they can encourage us to remember all those who were involved and all those who suffered. They remind us why we should never go back.

Senior Service Speeches

Emily - Art has always been a lens into history, particularly at times of conflict. As early as the famed Bayeux Tapestry relaying the events of 1066, we see art’s early purpose as documentation, recording successes and remembering events on behalf of future generations. However, in the last century, art has moved far beyond simple record keeping. War artists document conflict through direct observation, creating visual records that help people understand the reality of war. Paul Nash and his brother John were both appointed as official war artists, and like them, Doris Clare Zinkeisen and her sister Anna were also commissioned.

In the order of service in front of you are two images of paintings, the top image a painting by Paul Nash, the bottom, by Doris Zinkeisen. Look at the image you’re holding, what do you think?

For me, and my ideas about what the war may have looked like, it's not immediately explicit enough. There are no dead bodies, or blood or even weaponry shown. Its a bit unexpected, and maybe a bit more boring than the action movies we are so used to seeing. Ultimately, you’re probably thinking...this is a few dead trees, on a field, probably saying something trivial about hope. And they have definitely chosen this with the intention of a ‘school friendly chapel’ in mind.

As an art history student I am obligated to disagree.

I think with the invention of photography, we have these disturbing images already.

The painting is titled We Are Making a New World, and specifically captures the aftermath of the First World War. Rather than showing soldiers in combat, Nash presents an eerily quiet landscape. His battlefield is stripped bare, trees shattered and earth wounded by shellfire. Notice how there are no soldiers. The scene feels still and focuses on nature, as if it is pausing to mourn. In the distance is a pale light that breaks over the horizon, here Nash does suggest something about renewal. Even in ruin, everything starts again, beneath the trees is green, evidence of new growth.

His work aims to show a soldier’s perspective, the scene is exhausted. It makes you feel tired, with its muted colours and lumps of churned land making the image physically harder to look at. Your eyes have to follow the lumpy outlines to take the

image in. Perhaps the dead trees do soften the harsh reality of death and do stand in as more swallowable symbolism for our fallen soldiers.

Or, his choices permit a new form of understanding. Its very hopeful, Its quite a lovely picture. The land he shows becomes a sort of witness to the conflict. Its healing and maybe that’s just as important.

Sylvia - Doris Clare Zinkeisen’s C-Ward 101 of the British General Hospital, Louvain presents a vision of war that is both deeply reflective and quietly redemptive. Painted in 1945, after Zinkeisen had served with the Red Cross in Europe, it depicts a hospital ward filled with wounded soldiers recovering under the care of nurses. The light in the painting is striking — a soft, golden illumination that spills across the crisp white bedsheets and polished floor, transforming the ward into a place of serenity and grace. The careful composition, with its rhythmic arrangement of beds and calm sense of order, conveys not chaos but composure. Though every figure in the room has witnessed horror, Zinkeisen paints them not as broken, but as dignified — survivors rather than victims. Her dual identity as both nurse and artist gives the painting its rare tenderness and credibility: she knew the true cost of war, yet chose to dwell on the moments of compassion and care that quietly redeem it.

Unlike Paul Nash’s We Are Making a New World, where a ravaged landscape testifies to war’s futility and moral desolation, Zinkeisen’s scene inhabits the fragile aftermath — the moment when healing begins. Her use of light feels almost spiritual, as if divine grace enters this most human of spaces. The painting reflects not just physical recovery, but a moral and emotional one: a reawakening of faith in humanity’s capacity to mend what has been broken.

War artists like Zinkeisen remind us that art has the power to both confront and contain atrocity. Through their vision, we are invited to look upon suffering, to acknowledge it, and yet to find within it the resilience of the human spirit. C-Ward 101 of the British General Hospital, Louvain becomes, in its own way, a kind of chapel — a sacred space of compassion, reflection, and quiet hope. It teaches us that remembrance is not only about mourning the dead, but also about honouring the living: those who tend, who heal, and who continue to find light in the shadows of war.

As we pause today to remember those who suffered and sacrificed, these images urge us to do more than look back. They call us to see — to see the cost of conflict, the endurance of compassion, and the quiet beauty of renewal. For remembrance is not only about the silence of loss, but also about the courage to rebuild; not only about mourning the fallen, but about continuing their legacy of care, peace, and humanity.

May we carry that same spirit forward — to heal where there is hurt, to hope where there is ruin, and to remember, always, with hearts that choose compassion.

#StPetersSeniorSchool #StPetersHistoryofArt #StPetersValues #StPetersInterests

.jpg&command_2=resize&height_2=85)